Going Up to Atlanta

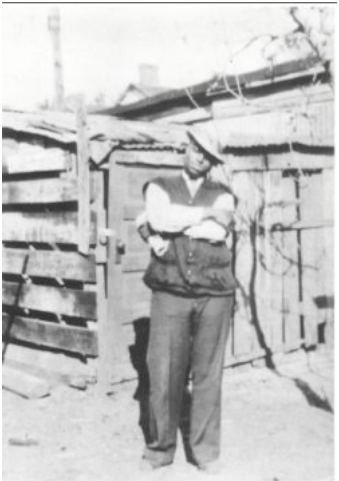

James Allen McPherson, Sr., 1913-1961

This is the only picture I have of my father. It was taken sometime in the 1930s, at his mother's family home in Hardeeville, South Carolina, when he was a young man. I have known all along that he liked comic books. Someone has pointed out to me that he is wearing a down jacket. The wearing of down jackets did not become fashionable until many years after this picture was taken. But a down jacket would be most comfortable during the cool, rainy winters that settle into the coastal areas of Georgia and South Carolina. My father's roots were in this region. Knowing its climate, he must have dressed with an eye toward comfort.

Someone else has noted that he seems arrogant. I cannot remember him this way, although some arrogance, for him, was possible. But most likely his arms are crossed and his eyes are closed and his head is tilted because he is asleep. I have learned that he suffered from narcolepsy, an inherited disorder that causes a person to fall asleep at absolutely any time. My brother, Richard, inherited this condition from my father. I note that my father has small hands. This is surprising, considering the fact that he labored all his life as an electrician. I want to believe that he was not fated to be a laborer.

When my father died, in late December 1961, I had just returned to Savannah from Morris Brown College in Atlanta. In my own mind, my father had died many years before. I attended the funeral, but grew angry when the Methodist minister who conducted the services said, "We all knew Mac, and we all know he's better off where he is now."

I did not attend the burial.

Moving Pictures

In California, many years ago, I saw a Japanese film called Sansho the Bailiff. The film is about Japan during its Middle Ages, when slavery existed as an institution. It tells the story of a family.

The Governor of a certain province, who is an aristocrat, decides on his own that human slavery is wrong. He decrees its abolition. But the decree threatens the human property of Sansho the Bailiff, who is the most powerful slaveholder in the province. The Shogun immediately revokes the Governor's decree, because it threatens to undermine the social order, and transfers the offending Governor to a remote province, where his personal feelings about slavery will pose no threat. The departing Governor sends his family, a wife and two children, to live with her parents. While traveling, they are kidnapped by slave traders. The mother is sold into prostitution. The two children are sold to Sansho the Bailiff. They grow up as slaves. The son becomes dehumanized and loses his memory of his former life and therefore his iden- tity. He becomes such a good slave that he is promoted to the rank of trustee. It becomes his job to mutilate, kill or bury any slave who tries to escape or who dies of work or of old age. During one trip outside the slave compound, a very beautiful thing happens. The young man and his sister are gathering branches in order to bury an old woman. They have to break some branches from trees. They both pull at a branch together. It breaks and they fall down. The fall is a repetition of a similar fall they had, as children, when they were gathering branches for a fire the night the family was captured by slave traders. This ritual gesture, recalling the last happy moment they shared before becoming slaves, revives the young man's former psychological habits. He begins, slowly, to reclaim himself. His sister, at the sacrifice of her own life, eventually helps him to escape. He eludes the slave catchers and, after great difficulty, petitions the Shogun to restore his family name. Recognizing the offspring of his former official, the Shogun makes the young man Governor of the province. He now occupies the same position as his father, who by now is dead. The son immediately issues a decree outlawing slavery. Whereas his father, an aristocrat, had outlawed slavery out of his own intu- itive distaste for the institution, the son, having been a slave, has an earned contempt for the dehumanizing aspects of the institution. Even though his sister is dead and his mother is now an aged, mutilated prostitute, the son does achieve the father's original desire. But he achieves it for reasons that are personally and emotionally sound.

He learns.

I learned from this film that, among the Asians, the offspring can ennoble the ancestor.

In Atlanta

My father's half brother, Thomas McPherson, Jr., is closer to my age than he is to my father's. He was born, during my grandfather's second marriage, after my father had achieved adulthood. James Allen McPherson, Sr., my father, was himself like a father to Thomas McPherson, Jr.

In the late 1960s, Thomas, a trained minister, became District Director of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. His office in Atlanta covered Georgia, South Carolina and Alabama. I visited him there once and met some of his employees. One especially cheerful older white man was very pleased to meet me. His name was Bill Harris. My uncle Thomas introduced us, and explained that Bill Harris, because he was once Sheriff of Chatham County, Georgia (which included Savannah), once knew my father very well. Bill Harris had arrested my father many times, not for any personal offense but for "cheating and swindling," for not completing work he had contracted to do. Bill Harris shook my hand and said, "Everybody liked Mac. It's just that he couldn't hold his liquor."

I remembered Bill Harris. I remembered one night he came to our house to arrest my father. I was about six. My father had come home to say goodbye to us. His ambition had always been to go up to Atlanta and start over. He had come to see us one last time before he left Savannah. We lived on the top floor of a duplex at 509 1/2 West Walburg Street. It was a cool winter night, in December, and we had no lights or heat except for the fireplace in the bedroom. For light we used candles and an oil lamp. I remember the four of us, and my mother, standing at the top of the stairs. Mary, my older sister, was holding the lamp. All of us were crying while my father said goodbye. Just as he turned to walk down the stairs, the front door opened and Bill Harris, the Sheriff of Chatham County, came in the door and said, "All right, Mac, get your hat."

I think now that if he had not loved us enough to come to the house to say good-bye, he would have gotten away.

Augusta

Thomas McPherson, Sr., my grandfather, lived at 1635 15th Street in Augusta. I associate Augusta with Christmas.

Thomas McPherson, Sr., was for most of his life an insurance salesman for Guaranty Life Insurance Company. He married twice. His first marriage was to Alice Scarborough of Hardeeville, South Carolina. That marriage lasted until shortly after my father was born. His second marriage, when he was in middle age, was to Josephine Martin of Blackshare, Georgia. She was my mother's first cousin. By this marriage he had two children, Thomas and Eva, and moved from Savannah to Augusta. There he led a poor but respectable life. In Savannah, we lived almost always in poverty: public welfare, clothes from the Salvation Army, no lights or heat for years at a time, double sessions in the segregated public schools, work at every possible job that would pay the bills. Each year at Christmas, if my father was not with us, my grandfather would try to arrange to bring us to Augusta, so we could share the family Christmas at his home. Sometimes we would go by train. Other times he would try to arrange a ride for the four of us with the insurance men with whom he worked. I can't remember whether or not my grandfather owned a car.

When I think about Augusta, I remember ambrosia. It was made with coconuts, apples, pecans, oranges and lots of spices. It would be served with Christmas dinner, late at night, when people would not notice the small amounts of food. But in the mornings, there was the anticipation of toys. Sometimes we would get old toys that had been repaired by Thomas and Eva. Thomas had a chicken coop in their backyard, and he liked to show me how, with the sound of his voice, he had trained the chickens to cut off and on, off and on, the light in their coop. He had a bicycle, and would take time to ride me on the back seat of it before he went to work. Once, when I had a very bad cold, Thomas bought a lemon for me. I remember that lemon after all these years because the gesture was grounded in love.

I also remember my grandfather, who had a nervous condition, sitting at the head of the table and moving his hands up and down, up and down, to steady his nerves. After the meal, which was the high point of Christmas Day, he would say to his wife, "Joe, I enjoyed the meal." And she would answer, "I'm glad you did, Mr. Mac." Afterwards, before it was time to go to bed, I would sit alone in the living room and draw Christmas trees. I had, then, great talent as a drawer of Christmas trees. I still love trains because sometimes we would take the Nancy Hanks, run by the Georgia Central Line, from Savannah to Augusta.

Janie McPherson

“Aunt China”

Whenever I ran away, I would get as far as Aunt China's house. I would say, 'Aunt China, I'm running away." She would look severely at me and say, "What's wrong with you, boy? Here, sit down and eat some of these greens and rice." I loved Aunt China. She was the wife of Robert McPherson, my grandfather's brother, and lived on West 32nd Street in Savannah. I think she was pure African.

My Uncle Bob, Robert McPherson, was only one of my grandfather's brothers. The others were Joe, B.J. and George. My Uncle George, whom I never met, was a Presiding Elder in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. The family agreed that he could preach the fuzz off a Georgia peach. Uncle Bob and Aunt China were like parents to my father. I think now that he must have run away to their house many times, even after he was a full-grown man. I know that, when I was a boy, I could always find out where he was if I went there.

Aunt China was a very strong woman. She never asked "real" questions, but seemed to know everything. She seemed never bothered by anything in life. All of us leaned on her, absorbed her strength. She seemed to assume that everything in life could be cured by a good meal and a good night's sleep. I liked to go there when I ran away.

Several days before my father died, he sent word that he wanted to see me. He had been living in a rented room in 33rd Lane, just a few blocks away from Aunt China's house. I did not go to see him. But when the news came that he was dead, I ran away to Aunt China's. This was one of the few days when she was not at home. I was making up my mind to go on to the rooming house where my father had just died, and I was walking down 32nd Lane, when I saw Aunt China coming up the lane toward me. Down the lane, in the distance behind her, I could see an ambulance loading my father's body. It was the only time I ever saw my Aunt China cry. She took me home with her and kept crying and saying, "I told that fool. I told that boy."

Houses

The stable houses were Aunt China's on 32nd Street and wherever my Aunt Beulah Collins was, anyplace in Savannah. The others were places we lived.

We lived at 509 1/2 West Walburg Street, next door to a funeral parlor, from the time I was born until 1951. Then we moved to 2010 West Bulloch Street and lived there until 1953. Then we moved to Green Cove Springs, Florida, for a summer. Then we moved back to Savannah and lived there with our cousin, Cassie Harper, until 1955. Then we moved to the east side of town, into a small apartment at 508 East Henry Street. In 1957 we moved to 1006 1/2 Montgomery Street, into a duplex owned by an electrician named T. J. Hopkins. We lived there until 1960. Then we moved to 316 West Hall Street, about five blocks away. In 1963 my mother moved into a housing project named Catton Homes.

During all this time, I liked Aunt China's house the best. I could always go there from the other places. Of the other places, I liked the duplex on Mont- gomery Street the best. The adjoining apartment was vacant, and I could get into it through a hole in the closet of one of the bedrooms. I liked to crawl through that hole, sit on the floor in the empty, quiet apartment and be alone.

Ebony, North Carolina

Eva McPherson (Clayton)

In 1980, I went to North Carolina to see Eva, my father's half sister. She is a very successful woman and was, at that time, a County Commissioner. Except for brief exchanges at funerals, I had not seen her since I was a child.

I asked Eva about my father. She told me that he was considered a "brain." She said that, in his day, he was the only licensed black master electrician in the entire state of Georgia. I asked her what had happened to him. She said she did not know. I asked her whether he chased women. She said that he was a faithful husband, but liked to drink and gamble. She said his only real love was electricity. She said that he had invented a device once that, when placed over an outlet, would reduce the cost, but not the flow, of electricity.

She said that the officials threatened to take away his license if he ever tried to market it. She said that I was not the first in my immediate family to attend college. She said that my father had attended the same college I finished, Morris Brown College in Atlanta, but had been expelled after the first semester for gambling. She said that, during-World War II, he had been deferred from active service because he taught a course at Savannah State College, a course in engineering, that was considered essential. She said that he was a completely self-taught man, having never attended any grade beyond one college semester. I asked Eva how it was that such a gifted man could wind up dying of frost exposure in a rented room in a dirt lane in Savannah. Eva said she did not know.

I told Eva that I believed my father had been frustrated by having his license taken from him and by having to work for an older man, T J. Hopkins, as a common electrician. I told her that I believed that my father had considered Hopkins a father-substitute, against whom he was always rebelling. Eva said this was inaccurate. She said that the older man, Hopkins, had been my father's student. She said that Mr. Hopkins had never been a master electrician, only a licensed one, and that my father had never wanted to work for him. She said that his ambition, always, had been to start his own com- pany in Savannah or in Atlanta. 1 asked her why I had never been told these things.

Eva said she did not know.

Samuel James Collins, Jr.

“Bro”

Sam Collins is the oldest son of Beulah Collins, my mother's sister. It was Beulah Collins who drew my mother out of Green Cove Springs, Florida, and into Savannah. Beulah had left Green Cove Springs to marry a man named Samuel Collins who lived in Savannah. He was an ice-man by trade. He sent so many letters to Mary Smalls, my mother's mother, back in Green Cove Springs, letters that kept reciting the line "Beulah and me is having a wonderful time. We eat collard greens every day," that Mary Smalls became suspicious. She sent my mother, the oldest daughter, into Savannah to see about Beulah. While there she lived with her first cousin, Josephine Martin, who had just married a man named James Alan McPherson

McPherson, the grown son of my mother's cousin's new husband, was sitting around the house reading comic books. My mother never went back to Green Cove Springs. Samuel and Beulah Collins had four children: Barbara and Lucille, Sam and Harry. When we were growing up we were as close as brothers and sisters. I loved their mother with them. There was always laughter and life in their house. Sometimes, at Thanksgiving or at Christmas, when we had nothing to eat, Beulah would steal a can of mackerel for us from the family for whom she worked. My mother would make mackerel croquettes. But the best things about my Aunt Beulah's house were the magical things that happened on weekends. I would go there on Friday evenings and would not have to leave until Sunday night. Bro would tell me some of the things I could not have learned on my own.

We were not as close after we became adolescents. I had to work all the time, and go to school. My world was made up of school and jobs and reading. Bro moved into the street culture. In this way, through word of mouth, he came to know my father much better than I did. He joined the group of men who stood around the fire on the corner of Anderson and 31st streets. My father was also part of that group.

Years later, Samuel Collins told me that the men around the fire used to call my father "Papasqualli," their version of a Creek or Cherokee word meaning "Chief." He said that whenever the men had an argument, before they came to blows over the issue in dispute, one of them would say, "Well, let's go ask Mac." He said my father would delight the men around the fire with his command of language. He would say things like, "I think I shall repair to the bathroom." Samuel Collins said that, once, when one of the men said something negative about my mother, my father picked him up and threw him into the fire. He said that, usually, my father was a gentle man.

T.J. Hopkins

Called "Major" publicly by influential people in the white community, Mr. Hopkins was the only other licensed electrician in Savannah who was black. He had served in the U.S. Army, had attended school. He was always willing to employ my father, to give him a job as a common electrician. Once, after my father had gotten out of prison and had resumed working for him, Mr. Hopkins rented my father an apartment in his duplex just over the office of his company at 2010 Montgomery Street. My father had only to go downstairs to work and back upstairs to his family. Mr. Hopkins even allowed my brother and me to work for him, sorting electrical parts and cleaning out his office. In this way we could help our father pay off the rent. Nights, Mr. Hopkins sat at the main desk in his office talking on the telephone. Seated in the white glare of the neon lights, he looked, to anyone watching through the plate-glass window, like an actor on stage.

But my father was always losing his temper and quitting the job. His ambition was to regain his old license as a master electrician and start his own company. He had tried this many times and had always failed. Many of the men who worked for Hopkins were former members of my father's old crews. They were still loyal to him. Sometimes, a few of them would quit when he quit, and would not go back until he was forced, by family pressures, to go back. Mr. Hopkins was always willing to take him back.

But my father's ambition, always, was to regain his license and then go up to Atlanta, where he could start his own company.

Reidsville

The people at Reidsville would always welcome my father back. He was not a criminal, but many of the hardened criminals there loved him. My father was a great cook, and was always assigned to the kitchen. I think he was considered too valuable to waste on the road gang.

We used to go from Savannah to Reidsville to see my father. I was always very ashamed to see him come into the visiting room because there was a wire screen between him and us. But at the same time I was glad to see him. We always wore our best clothes when we went to Reidsville. My father, because he worked in the kitchen, gained weight there. He was always healthier after he had settled into the routine of prison life. But during one of his last stays, they gave him electric shock treatments. When he came back to Savannah, after that time, he went back to work for Hopkins without complaining. But he began to drink almost all the time. Sometime after that, when I was twelve or thirteen, I stopped trying to see him. If I saw him on Anderson Street after school, I would turn and walk the other way.

The last time I saw my father alive, I was seventeen. I had gotten a National Defense Student Loan and was about to go to college in Atlanta. I went looking for him one night and found him, standing by the fire, on the corner of Anderson and 31st streets. I had, by this time, been working every possible kind of job to help support the family I thought he had abandoned. During all my years in Savannah, I had never had peace or comfort or any chance to rely on anyone else. I blamed him for it. I was very bitter toward him. That night I lectured him, telling him to straighten himself out, as I had, and be a man. He said he was hungry and wanted something to eat. I bought a meal for him with money I had earned on my own. After he had eaten it he said to me, 'And a little child shall lead them."

This was the last thing he ever said to me.

Hardeeville, South Carolina

Eliza Moore

Mary and I drove from Virginia to Savannah in late 1980 to see about our mother. On the way back, we stopped off in Hardeeville, South Carolina, to see our aunt, Eliza Moore. She was my father's aunt, the sister of his mother, Alice Scarborough. After my grandfather and her sister divorced, Aunt Liza grew embittered toward our family. We never knew the reasons.

When we walked into the house she said, "You look just like James Mc- Pherson." Later, she brought out a number of pictures she had been saving for years. She gave me a picture of my father. She showed us pictures of Alice Scarborough. My grandmother was very beautiful. In every picture she was elegantly dressed. Her second husband, the man she married after my grand- father, was also elegantly dressed. Alice Scarborough was a mulatto. Aunt Liza explained that her family had been in Hardeeville since long before the Civil War. She gave me the ancestral names: Scarborough, Strains and Wattley. She said that some of the white descendants of these families still lived in Hardeeville. She told me that we had small shares in the property on which she lived. She said that James McPherson had been recognized as a "brain." She did not know what happened to him, although she had her suspicions.

Alice Scarborough

Green Cove Springs, Florida, 1953

John Smalls

My one memory of my mother's father is of him sitting in a wheelchair on the porch of his home in Green Cove Springs. He was tall and thin and stern- faced, and was squeezing two red rubber balls. He was, at that time, recovering from a stroke. My mother presented each of her four children to him as we walked up the steps. He asked each of us our names. When I said, "My name is James Allen McPherson, Jr.," he looked down at me and said, "You are not welcome here."

John Smalls had been a sharecropper in Blackshare, Georgia, when my mother was born. Before that, he had apparently moved between Florida, South Carolina and Georgia, working on plantations. He had two sons and five daughters: Bill, Joe, Mable, Beulah, Martha, Mary, Suzie. My mother, Mable, was the oldest of his five girls. My aunt Suzie, who now lives in Detroit, maintains that one of her father's uncles, Robert Smalls, was a Repre- sentative from South Carolina in the U.S. Congress during the Reconstruc- tion. She maintains that she has a book about his life. My mother has consis- tently denied this. She has never talked much about her background.

Both John Smalls and his wife, Mary, were of the Seminole people. Their ancestors were the runaway slaves and free black people and Creek and Cherokee who fled to the Florida swamps, in the early nineteenth century, to form their own nation. There, they continued their struggle for freedom. The U.S. government finally surrendered to the Seminole people in the early 1970s.

My mother told me that, when he was a sharecropper in Blackshare, Georgia, my grandfather was given the job of a white overseer. The owner of the plantation fired him. The former overseer swore he would come around and kill my grandfather. My mother said that she was a child then, and could remember her father sitting all night on the porch of their house, with a shotgun on his knee, waiting for the white man to come back. Since then, I think, my mother has always run away from trouble.

When I met him that summer in Green Cove Springs, John Smalls was the wealthiest black man in town. He owned several farms, a general store, a service station, and a number of houses. I don't know how he acquired this wealth, but I believe he worked very hard for it. My mother's mother, Mary, had died some years before, and my grandfather's second wife, Miss Annie, was in charge of his health and his property. I think she must have felt threatened by my mother and the four children she had brought home from Savannah. We had been evicted from our apartment, our furniture had been repossessed, our parents were separated, and we had no place else to go. Almost every week that summer my grandfather would say he wanted to go into Jacksonville so he could change his will. Miss Annie never set a date for the car trip. Finally, my mother left us in Green Cove Springs and went back to Savannah. She got a job as a domestic and a room for the five of us with her cousin, Cassie Harper. Then she came back and got us.

My grandfather never changed his will. When he died Miss Annie inherited all the property. My mother and her sisters never insisted on shares in the property. A few years later, Miss Annie sold all the assets and moved to New York.

Cousin Cassie Harper, 1954

I think that the happiest time of my life was when my mother returned to Green Cove Springs to get us and took us back to Savannah. I remember the five of us walking, one summer night, from the bus station on West Broad Street all the way to West 44th Street. I remember we were walking across a park to Cousin Cassie's house. We were holding hands. I think we sang. We sang songs we had learned at St. Mary's School and in Augusta. The trees were flush with thick green leaves lighted by the white moonlight. There was the scent of wisteria in everything. The whole park was dark and light and purple and green and thick-scented. The sky was absolutely clear and starry. I know we were singing.

Cousin Cassie's house was at 711 West 44th Street, in the middle-class section of the black community. We rented one bedroom, but were told that we had use of the entire house. Above us, on the top floor of the duplex, a woman named Sadie Stevens lived with Helene and Alreatha, her two daughters. There was a front porch with a swing. I liked to sit on the swing with Helene and sing popular songs to her. On our left lived Reverend Moore and his six children. They had a television set, and if I sat on the swing while their door was open I could watch whatever was on television. I especially liked Saturday and Sunday nights, when "The Toast of the Town" and "Walt Disney Presents" came on.

Cousin Cassie, though, was an embittered woman. She was a mulatto and had long gray-black hair that she liked to plait in two long braids while sitting on the edge of her bed. She always wore a flowing pink nightgown because she had severe arthritis that made it difficult for her to move. She had to spend almost all of her time in bed, and when she did walk it was with crutches. Root doctors in South Carolina had advised her that certain kinds of worms, fried and made into a salve, would relieve her pain. She had a huge skillet in which she fried worms almost all the time. She also had a great number of cats. Sometimes Cousin Cassie could be very sweet. Other times she was very mean. During the times when she was being mean, when we lived there, we did not go out of our room.

The five of us slept in the bedroom. My brother and sisters and I slept on one bed, while my mother slept on a cot across the room. We considered that room our home and did not take the rest of the house for granted. We were very careful to stay in our room when Cousin Cassie was being mean. We could tell she was being mean if we heard her coming down the hall kicking her cats out of the way with her crutches. No matter what she did or said to us, while our mother was at work, she would always try to make peace with us children before our mother came home. She would say, "We're all here together." And she would suggest that we go into the living room the next Sunday and pray together. We did this any number of times.

Cousin Cassie had an agreement with a man named Mr. Sellers, who was not very bright and who was totally alone in the world. In exchange for his wages from his work as a longshoreman, she agreed to cook meals for him. Most often my family and I did most of the cooking, except when Cousin Cassie insisted on serving him mutton. When she wanted to cook mutton we let her do it herself, because we could not stand the smell of mutton. It tended to linger in all the rooms of the house.

Cousin Cassie owned a number of houses on West 44th Street, and a number of houses in the lane behind it, and a lot of land in South Carolina. All of her relatives deferred to her. She had another agreement with Mrs. Eloise George, a niece who lived in one of her houses just next door to the one in which we lived. It was agreed that whenever Cousin Cassie needed something she would knock on the wall of Eloise's house and the niece would come over to help. In exchange for this, Cousin Cassie promised Eloise to leave her a considerable part of her property. Although this was the agreement, my family and Mr. Sellers did all the work for Cousin Cassie. We did it because we loved her, or were dependent on her, or were frightened of her.

During this time my grandfather, Thomas McPherson, Sr, died, and my mother developed an extreme case of ulcers. She was unable to work and would lie in bed, day and night, spitting up blood and in the most extreme pain. We thought she would die, too. She could not go to my grandfather's funeral. A guard brought my father in handcuffs from Reidsville. I watched the guard unlock the handcuffs so my father could approach his father's grave. Afterwards, the guard brought my father to Cousin Cassie's house so he could see my mother before going back to Reidsville. My father saw my mother moaning on her cot in our room and he began to cry.

When Cousin Cassie died, her niece Eloise and her brother began fighting over the property. This was what Cousin Cassie had wanted all along. She had always told us, "I'm not making a will for the dogs. When I die, I want them to fight over it." They fought for years. Both the niece and the brother approached my mother and promised her a house if she would testify, in court, for one or the other of them. My mother refused. The four of us—my sisters, my brother and me—pleaded with her to testify for someone, even though we knew that we had done all the work for Cousin Cassie, because we wanted to have a house of our own. My mother refused even us. Lawyers finally got all the property, through the manipulations at which they are so skillful. But a few years before Cousin Cassie died, my father came out of Reidsville again. He moved us into a small apartment on East Henry Street. He went back to work for T. J. Hopkins.

Dr. E. J. Smith

("Imhotep")

Dr. Smith delivered my sisters, my brother and me. Then he stepped back and watched us grow up. He and his wife had no children of their own, so he must have loved all the children he delivered. During his entire life, he never let go of us.

When we lived with Cousin Cassie on West 44th Street, he stepped back into our lives. He and his wife lived on West 41st Street, only three or four blocks away. He began inviting my brother and me around to his house on Saturday mornings. We were paid one quarter each to rake his lawn and clear it of dog shit. But the work assignment was only a ploy. Most of the time with him was spent drinking Postum in his kitchen. During these sessions he would drill into us the details of how he had worked his way through college, and then through medical school, as a waiter. He liked to recite the orders he had to call into the kitchen of the hotel in which he worked. He liked to shout, "One order of mulligatawny!" When we drank Postum, the three of us would toast our coffee mugs when Dr. Smith recited to Richard and me:

We've hit the trail together . . . You and I.

We've bucked all kinds of wind and weather . . . You and I. Although the years may bring success,

We'll know no greater happiness

Than knowing we have stood the test

OF FRIENDSHIP (click) You and I.

When I was ten or eleven, Dr. Smith took Richard and me down to the offices of the Savannah Morning News, the local paper, and asked that they give us jobs. He was told that we could have paper routes if we had bicycles. We had no bicycles. Dr. Smith took us to the Salvation Army Store, on West Henry Street, and bought two used bicycles for us. He then took us back to the offices of the Savannah Morning News and got jobs for us. We carried papers for years after that. When my bicycle was stolen, I carried them on my back.

When I was in college I thought a lot about Dr. Smith. By this time I was working, in Atlanta, as a waiter. I kept wanting to shout, "One order of mulligatawny!" But I never did. Instead, I returned to Savannah and went to see Dr. and Mrs. Smith. By this time he was old and sick, and did not seem to recognize me. I tried to give him back the money he had paid for the bicycles. He and his wife refused to accept it.

Comic Books

Like my father, I loved comic books. I think he must have introduced me to them. He knew a man, a white man, in Savannah, who ran a wholesale house specializing in comic books. The man must have been one of his customers. Sometimes, my father would take my brother and me there, and the man would let us climb into a huge bin full of remaindered comic books. We would "swim" in the bin full of old comics. The man would let us take as many as we wanted. I always liked the older ones. I remember "Buffalo Bug" because the dialogue was always in verse. I liked "Captain Marvel" and "Batman" and "Superman" and some of the detective ones. I liked "Little Lulu," too, because the last section was a serial about Little Lulu's adventures with an old woman named Witch Hazel. I liked the old "Tarzan" because it also had a serial called "Brothers of the Spear." I did not like the horror comics.

When we lived on East Henry Street, I used to play hooky from school and walk down to the Salvation Army Store on West Henry Street to see if they had any new old comics. Sometimes I would be able to buy them two or three for a nickel. I especially liked the fifty-two pagers, because they provided more story for my money. Over the years, I collected well over seven hundred comic books. I spent so much time at the Salvation Army, wandered up and down its rows so much, that I was considered a regular customer. The old white men who sat in the store, the bums and alcoholics, liked to see me come in because they knew where I would be going. If there were no new old comics, I would look at the books on the shelves next to the cardboard boxes of comic books. One day, I saw a leather-bound edition of the stories of Guy de Maupassant. A teacher at school, a woman named Kay Frances Stripling, had mentioned a story by Maupassant in our English class, and I saw it in the book. I think I paid a dime for a leather-bound edition of Maupassant's stories. I began to read them.

But I still liked comic books. Since I no longer had any interest in school, I would make every possible excuse to not get up in the morning. When my brother and sister had left the house for school, I would wander around town, looking for comic books. Once, I went into a drugstore a few blocks from our apartment and saw a rack full of new comic books. I wanted one of them, but did not have enough money. The comic book rack was near an enclosed telephone booth. I went into the booth and reached my hand out and took several comic books off the rack, and pulled them into the booth. I closed the door and wrapped the comic books around my ankles, over my socks but under the cuffs of my pants. Then I opened the door of the telephone booth and walked out of the store. I walked as casually as possible back to our apartment, and then hid in the closet for well over an hour. Then I tried to read the comics I had stolen. I could not read them. I finally wrapped the comics around my ankles, this time beneath my socks, and walked back to the drugstore. I went into the telephone booth and left them there. Then I walked out of the store again. I never went back into that drugstore for as long as I lived in Savannah. But soon after that, I began going to the Colored Branch of the Carnegie Public Library, up the block from our apartment on East Henry Street, and I would sit there all day reading books at random. When it was time for my brother and sisters to come home from school, I would go back to the house and cook a meal for them.

At one time, I had well over seven hundred comic books.

Affluence

Mary remembers that we were among the first black families in Savannah to have an electric stove. We also had a maid, a woman named Delphene, who used to help our mother with us and who used to give us baths. Mary also remembers that, at one time, my father had his own company and his own truck. It had painted on it: "McPherson & Company: Electrical Contractor." Mary also remembers that our father always gave us money when he came home from work on Fridays. She said that all the kids in the neighborhood would be waiting with us for him to come home. He always gave everyone a share of his earnings. But he would do it by ages, giving the older children more money. Mary said it did not seem to matter to him that his own children expected the best treatment. I do not remember these things. I remember, though, that my father always wanted a street in Savannah named for him.

I also remember attending the best school for "colored" children in the city of Savannah. It was St. Mary's, a Catholic school, on West 36th Street. All the teachers were white nuns. All the students were black. If you talked at St. Mary's when the nuns were out of the room, one of their spies would report you when they came back. Then the talkers had to hold out their palms so the nuns could smack them with a ruler. I never talked. I learned to read very quietly. I was never smacked.

My father always did more than anyone else to support the shows and parties that were put on at St. Mary's. He had a friend named Mr. Simon, a white man who ran an ice-cream plant. My father would always take my brother and me there to pick up five- and ten-gallon cartons of ice cream for the shows at St. Mary's. I think that Mr. Simon had affection for my father. They would always embrace when he went in there. The nuns were very happy to have the free ice cream. My sister, Mary, was always a star in the show.

During my three years at St. Mary's, I was trained to be a Catholic. Mary and Richard and I learned the rosary, attended mass, lit candles. But toward the end of my third year, the priest in charge of St. Mary's called us out of class and into his office. He told us that our father had not paid our tuition for some time, but that since we were such good students he was going to pay it himself. He pulled a wad of money out of his pocket and showed it to us.

I never knew whether my father paid what was owed to St. Mary's. Toward the end of my third year, and my sister's fourth, we were transferred from St. Mary's to the Florence Street School. The black children there had to attend double sessions: half went from early in the morning until noon, and the others went from early afternoon until five or six o'clock. I was put into group five, among the retarded people, during the last part of third grade and through all of fourth. I sat at my desk and never said a word. I read my sister's fifth-grade books on the sly.

Paulson Street School

After we moved to East Henry Street, I had to attend Paulson Street School. This was where all the mean people went. They would throw rocks at you, push you in the halls, trying to make you fight. I did not want to fight anyone. During the years at Paulson we were eligible for the free lunch program. This was available, through the state, for anyone on public welfare. Every six weeks, when he was making out his report, the teacher would ask me before the entire class, "McPherson, is your father still in jail?"

During those years at Paulson I developed a reputation for remotion. I just did not want to talk. Once, a boy named Leon Chaplin, who shared a desk with me, asked if he could sharpen my pencil with his new knife. I refused to give it to him. Leon insisted that I hand it over. I refused. He said that if I did not give him my pencil he would stab me. I refused to give it to him. Leon stabbed me, under cover of the desk, in the left thigh. I grabbed him and took the knife away. The teacher saw us wrestling and thought that I had attacked him. I told her he had stabbed me. She demanded to see the evidence. Because I would have had to take down my pants, I refused to show her the mark. After that I was watched.

During the course in first aid, we were required to demonstrate artificial respiration techniques. Our grades depended on our learned skills in this exercise. But during this time our mother was buying all our clothes from the Salvation Army, and there were holes in my shoes. For this reason, I refused to kneel down and demonstrate how much I knew about artificial respiration. I knew that the other kids would laugh at the holes in my shoes. I did not want them to laugh. The teacher kept demanding that I kneel down. I kept refusing. I finally flunked the course.

But during this same time, I discovered the Colored Branch of the Carnegie Public Library less than a block away from where we lived on East Henry Street. I liked going there to read all day.

Books

At first the words, without pictures, were a mystery. But then, suddenly, they all began to march across the page. They gave up their secret meanings, spoke of other worlds, made me know that pain was a part of other peoples' lives. After a while, I could read faster and faster and faster and faster. After a while, I no longer believed in the world in which I lived.

I loved the Colored Branch of the Carnegie Public Library.

"Daddy Slick" and "Mama Della"

These were people who had no respectability. They were my father's friends. They owned and ran a place on 32nd and Burroughs streets where men gambled and where moonshine whiskey was sold. I loved to go in there and look for my father. He loved to gamble and be in there with the other men.

To get into Daddy Slick's place, you had to walk through the dry black dirt on Burroughs Street until you came to a big yard enclosed by a high wooden fence. You could not look over the fence, but you could ring a buzzer on a wooden door in the gate. A peephole would open, and you had to say to someone, "Is my daddy here?" Once you were recognized, the wooden door

would open and you would be allowed into a courtyard where ducks and geese and flamingos and chickens were strutting and scratching in the black dirt. Directly across the courtyard was the house in which Daddy Slick and Mama Della lived. To the right of the house, at a distance, was another house, a much smaller house also made of wood. It looked almost like a toy house and was painted bright colors. This was where people drank and gambled. To get in, you had to knock on another wood door and be inspected through another peephole. Inside that place, it was always dark. But there would be music from a bright jukebox, and light from the pinball machines, and people would be drinking. Daddy Slick or Mama Della always sat behind the counter facing the door. They always saw you before you saw them. Daddy Slick was very fat and Mama Della was very thin. Daddy Slick always wore a round, flat touring hat. People said he had a photographic memory and never forgot anything, especially the amount of money people owed him.

He sat with his legs apart so his belly would have room to spread. He or Mama Della always gave you a Coke or an orange soda or a nickel or a dime. In the wall near the counter was another door. In that room people gambled. My father was almost always in there. I always wanted to go in there, but was never allowed to. I would have to sit at the counter and wait for him to come out. Sometimes I would play one of the pinball machines. When my father came out, he would always buy something for me, no matter whether he had won or lost in the gambling room. Once, because he had promised to buy me a television for my birthday, I played hooky from school and waited all day at Daddy Slick's for him to finish gambling. He had just won a lot of money playing bolita. But when he came out, in the late afternoon, he had lost everything. He could no longer afford the down payment on the used television set we had already chosen. He tried to give me his wristwatch instead. I refused to take it.

Daddy Slick also sold bolita. Someone told me once that my father won at bolita so often that after a while no dealer in town would sell him a ticket. But he was liked by all the men who spent time at Daddy Slick's. Whenever he was in jail at Christmas or at Thanksgiving, Daddy Slick or Mama Della, or one of the men, would bring a box of groceries to our house. These people had their own code.

Electricity

1957

I think that a certain kind of creative man finds one thing he likes to do and then does it for the rest of his life. I think that if he is really good at what he does, if he is really creative, he masters the basics and then begins to play with the conventions of the thing. My father was a master electrician.

During one of the times he came back from Reidsville, we lived on East Henry Street. He was working again for T. J. Hopkins, and was trying to be a man in all the conventional ways. He liked to cook for us, liked to drop by the house to see us whenever he passed it during work hours. He liked to fix things. One day he was repairing the light fixture above the face bowl in the bathroom. He asked me to hold one of his hands and to grip the faucet of the bathtub with my other hand. I did this. Then he licked the index finger of his free hand and stuck it up into the empty socket where the lightbulb had been. As the electricity passed through him and into me and through me and was grounded in the faucet of the bathtub, my father kept saying, "Pal, I won't hurt you. I won't hurt you." If I had let go of the faucet, both of us would have died. If I had let go of his hand, he would have died.

That day, I know now, my father was trying to regain my trust.

Black and White

Once, when a story about me was in the Savannah papers, an old white man called up my mother. He introduced himself as a former Chatham County official who had known my father through his work as an electrician. My mother said he asked, "Is this Mac's son?" Then he said, "Mac was a brilliant man. That liquor just got to him." Then he said, "Mable, I never had anything against the colored. Now both of us are old. Can I come around sometime and sit with you?"

Richard, my brother, knows more about the public side of my father than I do. He and my father worked together on a number of jobs. He told me that when they were wiring a store for a Greek on East Broad Street, my father's and my brother's skills came under the watchful eye of a redneck. He and his son were pouring concrete for the Greek. The redneck watched my brother for a while, and then said to his son, "You see there? If you worked as hard as that little nigger over there you'd get someplace." Richard said he turned to my father and saw him laughing. The sight of this, considering the insult, made my brother cry. Then my father said to Richard, "Look, if you get hot over something like that, you'll stay hot all your life."

Richard also told me that part of his job with my father was to take certain papers to a state agency as soon as a job was completed. He said there was a receptionist's desk in the lobby of the building to which he was required to go. This was during the time of official segregation, and the white female receptionist would always stop him at her desk and try to prevent him from going upstairs. But then the official in charge of the agency would come to the head of the stairs and say, "Is that you, little Mac? Come on up." He would sign the papers without looking at them.

The Jewish community of Savannah, which was old Sephardic, knew and respected my father for his intelligence and skill. They knew who his children were. Sometimes on Christmas Eve, when our lights were off and we had no food or presents or Christmas tree, my father, if he was not at Reidsville, would appear well after dark with money he had either borrowed or won at gambling. He would break the law by turning on our electricity himself, and then he would take us downtown to shop. Certain merchants would keep their stores open for him far past closing time on Christmas Eve. I never believed in Santa Claus, but I believed that my father, sometimes, possessed a special magic.

Last Christmas my mother gave me the best Christmas present in the world, and all Christmas Day I felt as if my father were still keeping the stores open late on Christmas Eve. She said he loved to buy groceries after he had been paid for doing a job. She said that one night he came home with sacks and sacks of groceries, bought with money he had just collected from poor white people for work completed. He told her, "Mable, those people don't have anything. They paid me because they're proud. I'm going to take half of these groceries out to them." Since my mother valued security, she said, she got very mad.

Wendell Phillips Simms

Mr. Simms ran a fish market on the corner of West Broad and Walburg streets. His father had been a slave who escaped to the North during the years just before the Civil War. He had joined the abolitionists, had taken the name Wendell Phillips, and had returned to Savannah during the Reconstruction. He brought the traditions of freemasonry into the black community of Savannah. His son, Wendell Phillips Simms, was a thirty-third degree Mason. I did not know this when I was growing up.

Mr. Simms had five children: Robert, Ruth, Merelus, Louis and Richard. Merelus and I were born on the same day, next door to each other. We were natural playmates. Mr. Simms and my father, in the early days, exchanged turns taking us to school. But after a while, they did not get along. The clash of personalities, I think, resulted from the differences in their perspectives. My father seemed to love everybody. Mr. Simms had deep suspicions of the world outside his fish market. My father drank and gambled. Mr. Simms did not. My father was always looking out for other people. Mr. Simms looked out for himself. My father took great chances. Mr. Simms always hedged his bets. My father improvised. Mr. Simms practiced great efficiency. Mr. Simms did not seem to respect my father. Whenever he spoke to me of him, I could hear condescension in his voice. Mr. Simms thought, long before I did, that my father was irresponsible.

When I went into their fish market, after school, I would talk with Merelus and Louis while they cleaned and weighed fish. Mr. Simms would recite poems like "Invictus" and "Keep A-goin'" while he cleaned fish. He knew all the nineteenth-century declamatory gestures. He seemed to believe the words he recited. He practiced great self-reliance and had a quiet contempt for Christianity. He kept his contacts with white people to a minimum. He pre- ferred to catch his own fish in the Savannah River rather than buy them from the local wholesalers. He once attacked a truckload of Klansmen with a crowbar.

When I was about six, Mr. Simms began making bricks. He designed a device in his backyard for pressing and baking cement blocks. Over the years, day after day, he and his family made thousands of bricks. They tore down parts of their house as more room for the bricks was required. I liked to watch them from our kitchen window. Merelus and Louis and Richard would climb up the pyramid of cement blocks and talk with us through our kitchen window. My father agreed to do the wiring for the new house, and I wanted very badly for him to have some part in the creation. But by the time the house was ready for wiring he had lost control of his own life. Mr. Simms finished the house, by himself, and moved his family into it. I was invited there to visit a number of times. Mr. Simms had broken his health completing the house, but he was very proud of what he had done. When he spoke of my father, there was that familiar contempt in his voice. He died, in the house, shortly after he had settled his family into it.

Several years later, the Urban Renewal leveled the entire west side of Sa- vannah, including Mr. Simms's house, to make room for a massive housing project named Catton Homes.

Mr. Hopkins under the Neon Light

We owed Mr. Hopkins many hundreds of dollars when we moved out of his duplex on Montgomery Street. He had offered to let us stay, and he offered to let my brother and me work for him, in the absence of our father, in order to pay off the debt. My brother, Richard, did work for him for a while, but then my mother found another apartment and insisted that we move. We moved into an apartment in a slum that had many rats. I could not understand why she had not accepted Mr. Hopkins's kindness.

Years later, when I understood, I thought that Richard should be the one to repay Mr. Hopkins the money we owed him. I wrote a check for a certain amount and gave it to Richard and asked him to go in and put the money on Mr. Hopkins's desk. I don't know whether Richard ever turned over the money. I don't know whether he ever understood.

In the Fish Market

Louis Simms is the third son of Wendell Phillips Simms. Unlike Merelus, he left Savannah. Like his oldest brother, Robert, he joined the U.S. Army and became an officer. He served in Vietnam, then in Europe, then returned to Savannah to be close to his mother. When Mrs. Simms died, he moved to Michigan to be close to his older sister, Ruth. Both he and I wound up in the Middle West, and we have a bond based on common memories. Louis remembers all the details.

Since childhood, Louis has kept everybody honest. He tells the truth, even though it hurts. Sometimes I feel that his father and my own are still debating essential issues: the advantages of efficiency over improvisation, the self- negation that can come from Christian belief, whether it is better to laugh at or to attack intruding Klansmen, whether it is best, or extremely dangerous, to call attention to intelligence and ambition in black males. Louis is wise in a pragmatic sense. He spent most of his boyhood making cement bricks.

Once, years ago, I was invited back to Savannah by the Poetry Society of Georgia. They asked me to give the Gilmer Lecture. It was a ritual occasion. The obligation of the exile is that, when he returns home, he must take something beautiful with him. At the time of the speech I had nothing to take home except forgiveness for my father. But to forgive him, I had to forgive the entire community. I wanted, twenty years late, to give a funeral oration for an intelligent and creative man. I wanted to say to the people, "This is a small part of the good thing that was destroyed." In the speech I gave I tried my very best to do this. My uncle, Thomas McPherson, was in the audience. He told me later, "James, you sure were generous to Savannah." But Savannah was also part of my father. I was trying to take the best parts of him home for burial.

Sometime later, I let Louis Simms read the speech. He called to my attention some of the concrete details that I had left out. He said:

“Although I followed the themes of your Gilmer Lecture—the merging of white and black cultures, your personal growth, the myth of racial classification, and change—I found some elements of the Savannah experience (the Southern experience, really) missing, and others, incredulous. I found it incredulous, totally unbelievable, that you could remember no specific incidents of oppression, to yourself or others around you. It is impossible for you to have been born in the South of the forties and not have experienced specific incidents of racial oppression. You may have suppressed those experiences in your subconscious, but they happened.

“You sharply forgot to mention that time and time and time again, your father had been unjustly denied an electrician's license—and he was the best. Yes, Mr. Mac was the best, or so my father and mother told me. My father and mother also told me, and my brother and sister, that the lily-white test administrators would never release your father's test results. This refusal by white folk to grant your father an electrician's license and release his test scores, along with scores of other rejections and humiliations—the inheri- tance of all black people—caused your father irrevocable pain. The pain may have even caused him to masquerade—as many unpleasantries have undoubtedly caused you to masquerade—his hostilities toward whites. He turned to drink for relief, you turn to ‘ideas.’

“Those black folk who did not have other escape mechanisms, had to masquerade, or face the sure prospect of being blown to pieces, physically and psychologically. Believe me, your father's alleged status as the first black master electrician in Georgia came at a terrible drain on his inner resources. His effort to become an electrician, much less a master electrician, was a great leap from the abyss of despair. I'm not talking abstractly now. Two years ago, I did a paper for an E.E.O. case in Labor Relations on 'Blacks and the Law in Skilled Trades.' The electrical trade was, and still is, more discriminatory towards blacks than any other skilled trade. The electrical trade, in fact, has almost totally excluded blacks. When writing this paper, so as not to become abstract, I thought of your father, Mr. Mac . . .”

The Ancestral Home

There is not one house where I lived as a child still standing. My family is scattered. All of us have, in one way or another, gone up to Atlanta. But my mother still resides in Savannah. Her one ambition, for many years, was to have us all come home. We went, whenever she was sick, but we could not stay there with her.

My brother lingered in Atlanta, biding his time. He has my father's genius for things electrical and mechanical. He is a mechanic for a major airline. For years now, he has been the only black mechanic in his shop. He once expected promotion to foreman of his shop. He took the standardized tests and outscored his peers. The rule was changed to make the election of a foreman democratic. He played politics, made friends, did favors. Finally, a somewhat friendly white peer told him, "Mac, your only trouble is your father was the wrong color." After every new foreman is elected, my brother still receives calls at his home during his off hours. These calls are from his peers, and they explain technical problems that they cannot solve. They ask, "Mac, what should we do?"

My brother, Richard, is "Papasqualli" now, up in Atlanta.

Many years ago, I tried to go back as close to Savannah as I could. As usual, my mother was calling all of her children home. It was my fate, on the way back to Savannah, to enter a time-warp in Charlottesville, Virginia. I lived, as an intelligent black male, through the first fifty years of this century. And when, some years later, I emerged, I found that I had learned, emotionally, every previously hidden dimension of my father's life. I love him now for what he had to endure. I am determined now, for very personal reasons, to live well beyond the forty-eight years allotted to him, in any Atlanta I can find.

Like all permanent exiles, I have learned to be at home inside myself.

A Positive-Negative

There is, I know now, in the hidden places of human nature, a lust for power over the souls and the talents and therefore the bodies of special people. I don't believe there was any of this craving in my father. He had a passion for something that transcended it. He loved electricity, loved to play with it, and must have found some connection with God within the mysteries of that invisible flow. His will to believe in this, I think, allowed him to maintain the illusion that people were better in fact than they are in life.

For forty-eight years, I want to believe, he practiced an enigmatic form of his own secular religion.

Obligations

Honor thy father and thy mother:

that thy days may be long upon the land which the Lord thy God giveth thee.

The Book of Exodus

Rachel Alice McPherson 1979-

James Alan McPherson was born on September 16, 1943 in Savannah, Georgia. He is a short story writer and essayist, and a recipient of the Guggenheim Fellowship in 1973. His books include Hue and Cry, Railroad, Elbow Room, A Region not Home, and Crabcakes. He won the 1978 Pulitzer Prize for fiction, for his short story collection, Elbow Room. He was the recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship in 1981. His work has appeared in twenty-seven journals and magazines, seven short-story anthologies, and The Best American Essays. In 1995, McPherson was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He was educated at Morris Brown College, Harvard Law School, The University of Iowa’s Writers’ Workshop, and the Yale Law School. He has taught English at the University of California, Santa Cruz, Harvard, and also lectured in Japan at Meiji University and Chiba University. He is now a professor of English at the University of Iowa.