For more than a century, writers have been including photographs and other images into their novels and volumes of poetry. At first, photographs tended to serve as illustrations, as visual equivalents to the nearby text. But with the birth of Dada and the Surrealist movement just about a century ago, some writers began to make the relationship between text and image deliberately fraught. Images were injected in literary works in order to disrupt, contradict, or otherwise complicate the text and force imaginative connections between image and text. Today, few readers of contemporary literature would be surprised to find a handful or even a few dozen photographs scattered throughout a book. As a result, there is a growing interest in trying to understand the relationship between text and image in works of literature. How do they affect each other? How do readers react?

I thought it might be helpful to look at five novels in which only a single photograph is used, which would let us examine a few of the different strategies that writers employ when they embed photographic images in their fictional narratives.

Photograph One: The Portrait

Jeff Jackson is a writer, playwright, and professor of film. His debut novel Mira Corpora (Two Dollar Radio, 2013) is a grimly beautiful coming-of-age novel that reminds me of Larry Clark’s infamous 1971 photobook Tulsa, with its insider’s vision of a group of teenagers whose lives centered around sex, drugs, and alcohol.

In Mira Corpora, a character named “Jeff Jackson” narrates several autobiographical episodes that occurred between ages six and eighteen, based on journals that he has kept. Then, in a chapter called “End” (which is not the actual end of the book) the narrator, who is now eighteen, performatively erases his journals backwards, from the very last word to the first, signaling the end of that segment of his life. As he concludes this act of erasure he declares that “the ghostly traces that cling to these pages are my true story.” This is just one of several suggestions by the narrator that the story we are meant to read is not entirely to be found within the words on the page.

The episodes that Jefferson recounts each have a nightmarish or otherworldly quality, including a forest inhabited by children who are ruthlessly hunted by adults known as “truckers.” Jackson uses a slightly claustrophobic GoPro style of narration, in which we witness nothing that is not directly known by the narrator’s own five senses. And what the narrator senses is a stark and cruel world. “The landscape feels like it has been stripped to its shadows, chewed clean by the darkness.”

While reading Mira Corpora (Two Dollar Radio, 2013), it helps to keep in mind the epigraph that Jackson quotes from Surrealist Paul Eluard: “There is another world, but it is in this one.” The relationship between real and imaginary, often described as a linear spectrum, is circular here, with the real and the imaginary, truth and fiction, continuously flowing into and through one another. The narrator repeatedly flees into the woods, into darkness, into drugs, always seeking safety, only to enter a scenario as bad as the one he left.

The trajectory of the narrator also moves in a circular fashion when, at the age of eighteen, he inherits and returns to the house in which he had been raised by a brutal, alcoholic mother – and from which he had fled years earlier.

In the final chapter, which serves as a coda to his autobiographical fragments, the narrator presents a very short story called “Mira Corpora,” which he describes as “my first fiction.” In this story, which symbolically employs elements pulled from earlier chapters, a night watchman whose shift is over goes to his local bar where he encounters a skateboarder – a “pale boy with stringy black hair and sunken spaniel eyes” – with whom he senses a strange camaraderie. He offers to help find the homeless boy a place to crash. As they head out into the night together, the reader is clearly being led to feel suspicious about the intentions of the night watchman. Suddenly the story turns 180 degrees, and the boy picks up a piece of pipe and clubs the night watchman to death. He rubs his eyes with the dirt from the pipe and immediately sees a “tantalizingly unreal... serene vista” in front of him. But then the boy also senses that he might be merely a character in a work of fiction. He realizes that if he were to reach out to grasp this vision “his hand will stab straight through the page.”

Jackson uses a single photograph in Mira Corpora in a rather straightforward way, except that it has been torn in half, with the two portions appearing at the beginning and the end of the book, forcing the viewer to circle back to the opposite end of the book to complete the image. The photograph shows the head and naked shoulders of a young, probably pre-teen boy. The boy seems to have a kohl-like substance blackening his eyes that gives him a goth look. The photograph has also been smeared in vertical wipes that have left a transparent gray residue across the image.[1] The two halves suggest a vulnerable and seemingly innocent street waif, the kind of child we fear for in the “Mira Corpora” story – needlessly, it turns out. Jackson uses the torn photograph to symbolically represent the psychological and social sundering of his damaged character “Jeff Jackson.” But the two halves do not quite add up to be a portrait. The photograph has been torn directly through the boy’s blackened eyes, which seems to diminish the viewer’s ability to derive a strong sense of personality from the image. I think Jackson has done this so that the boy becomes a type, not an individual.

Photograph Two: The Film Still

Like Jeff Jackson, Nicholas Rombes has a film background. He has written several non-fiction books about film theory and punk music, but here we will look at his first novel, The Absolution of Roberto Acestes Laing (Two Dollar Radio, 2014). Rombes’ noir-saturated novel is an exploration of images (both moving and still) and their relationship with truth. The title character is a disgraced, mildly paranoid, former film librarian whose downfall occurred years earlier when he when made a bonfire out of the only known copies of several rare films. He is belatedly seeking absolution for that act by agreeing to a confessional interview with a journalist from a film magazine, who, in turn, is narrating this book.

Throughout most of the novel, Laing passionately describes in detail the plots and film devices found in the films he burnt. (Naturally, all of the films in Rombes’ book are fictional.) Laing’s discussions are full of advanced film theory, which film buffs will probably read with relish. But at one point Laing digresses. He opens an old envelope and withdraws a photograph that Rombes reproduces in the novel.[2] It’s a photographic copy of a film still from a 1910 movie called “The Murderous King Addresses the Horizon.” It also happens to be the only existing evidence of this “forgotten film, by a forgotten director.” Instead of giving us an extended ekphrastic reading of this film as he has done with the films he destroyed, Laing gives us multiple “theories about what comes after the frame, in the way that we sometimes wonder what happens in the moments right after the instant captured in a photograph.” Some of these imaginary endings are based on popular silent film genres: there’s a “western” version, a “great train robbery” version, a “Civil War nostalgia” version, and a “domestic melodrama” version. Laing then provides a “darker” version and, finally, “the most horrendous – but also the truest – version.”

As a cineaste, Laing believes that a single film still is nothing more than one link in a chain of events across a certain period of time and is therefore open to a boundless supply of narratives and interpretations of what happens before and after the moment shown in the still image. But Laing is also convinced that there are also moments “between the frames” of certain films when the “undiluted truth” can flicker. “What I mean is that there was something there, in between the frames, something that wasn’t quite an image and wasn’t quite a sound. It was both and neither of those things at the same time. In other words, an impossibility, an impossibility that, because it expressed or represented a new way of being, had to be destroyed. An extreme, undiluted truth, that’s what I’m talking about.” For Laing, an “undiluted truth” is a truth that is “unaltered by perception” and is thus something that humans do not seem capable of handling. In Laing’s mind, the moments between the frames of the films that he felt compelled to destroy contained “expressions of pure nothingness. A nothingness that goes beyond nihilism, beyond philosophy, a sort of absence that’s so seductive and so powerful that to look upon it is to corrupt a part of your soul.” This fixation with what lies between the frames of a film is a curious echo of Jeff Jackson’s assertion in Mira Corpora that the real story is not entirely to be found in the words written on the page.

As Laing says these words I have just quoted, the narrator opens his wallet and produces a photograph that is not reproduced in the book. It shows an image of the narrator’s daughter who died of brain cancer ten years earlier when she was just eight years old. Staring at the photograph and finding that he still is unable to process the meaning of her death, he realizes that her photograph contains the same frightening power of “undiluted truth” that Laing saw in the films he felt he had to destroy. The narrator’s relationship with this image is rooted in a tragedy that lends the photograph a power far beyond what might actually be seen on the small square of paper that he holds. Rombes’ reticence to reproduce this seemingly much more important photograph made me think of Roland Barthes’ “Winter Garden Photograph.” In Camera Lucida, Barthes describes combing through photographs of his mother shortly after her death. He finally stumbles upon one that made him see “the truth of the face I had loved.”[3] He then proceeds to tell the reader “I cannot reproduce the Winter Garden Photograph. It exists only for me. For you it would be nothing... for you, no wound.”[4] In other words, neither the “wound” nor the “undiluted truth” is universal; it is personal.

Photograph Three: The Still Life

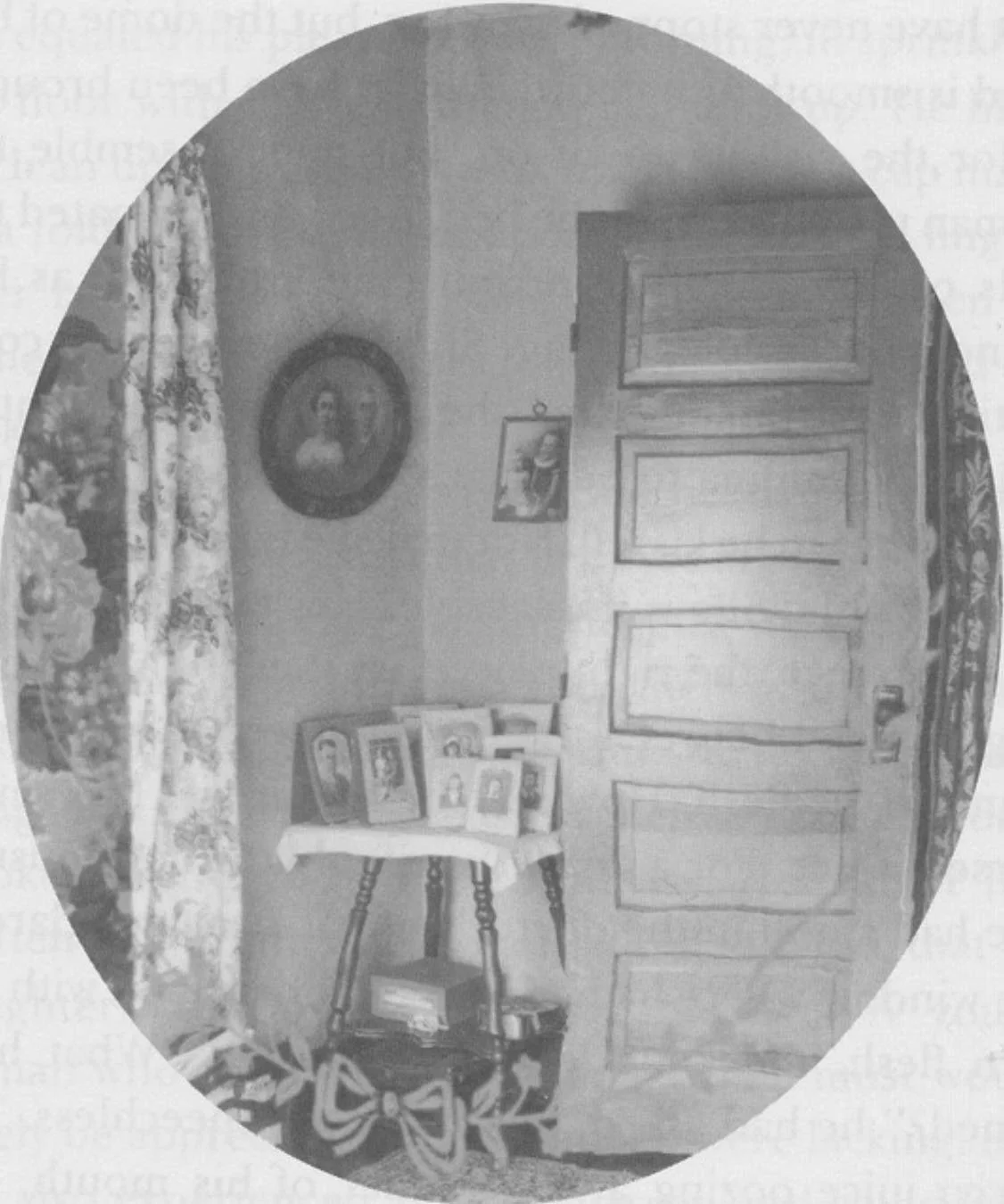

As far as I know, Wright Morris’s Plains Song (Harper & Row, 1980) is unique amongst novels with embedded photographs, in that it uses one photograph which repeats at the opening of each of the book’s fourteen chapters. The oval- shaped image depicts a mirror that reveals the corner of a room in a house. In the oval we can see curtains, a door, and a small table on which at least eight portrait photographs are on display. Two more photographs hang in the wall above the table. Mysteriously, upon closer inspection it becomes clear that the door is not a functional door but is actually leaning against one of the walls.

The novel begins with the story of two brothers – Emerson and Orion Atkins – who homestead in Nebraska around the beginning of the twentieth century, but it quickly shifts focus to the women who become their wives and then moves on the next two generations of daughters. Practical and uneducated men, Emerson and Orion acquired their wives just as they would acquire any other necessary supply. For them, wives were meant solely to cook, make a home, and breed children – preferably boys. The men in Morris’s novel are almost uniformly loutish, insensitive creatures with buckets of suppressed anger. What Morris does in this novel is to look through the eyes of the women as they struggle with their men, with raising families, with running a household, and with the isolation of rural life. But he also shows us how succeeding generations of women gradually liberated themselves from the limitations that their mothers and grandmothers faced. In Plains Song, Morris shows himself to be socially progressive writer with a strong feminist platform.

Wright Morris was both a successful writer and a highly respected photographer. His photography was dedicated to documenting the rapidly disappearing rural life that he experienced during his childhood in Nebraska, and thus nearly all of his images are concerned with everyday objects, interiors, and architecture. Two of his other novels – The Inhabitants (1946) and The Home Place (1948) – even went so far as to put words and photographs on an equal footing, with each book consisting of alternating pages of text and photography.

Plains Song is structured as a multigenerational family tree, and thus the photograph that is repeated throughout the book serves as a refrain that encapsulates the gist of this story, showing us a visual equivalent of a family tree that is formed by the photographs on the wall and the table below. The image’s curious oval shape immediately suggests that we are peering through a window or into a mirror rather than looking at a traditionally rectangular photograph. But we know that the shape is a mirror, both from the etched floral motif that curves up from the center bottom of the image as well as the title of the photograph from which Morris cropped the mirror: "Front Room Reflected in Mirror, the Home Place, near Norfolk, Nebraska (1947)." Morris correlates the subtle irregularity in the mirror’s glass to the imperfection of memory. He also notes that mirrors – and, by extension, photographs – convey only the visual or superficial aspects of people, not their souls, personalities, or invisible attributes. As Emerson’s wife examines herself in a mirror, she thinks that “the glass of memory ripples, or is smoked and darkened like isinglass... mirrors impressed her as suspect by nature of the way they presented a graven image.

She keenly and truly felt the deception of her reflected glance. Being a practical woman she did not forego mirrors, but they revealed so little of a person...”

Photograph Four: The Newspaper Clipping

Austrian writer Konrad Bayer’s Der Kopf des Vitus Bering: Ein Porträit in Prosa (Walter Verlag, 1965) is a deliberately fragmented, rambling, hallucinogenic prose work written in a collage format that allows Bayer to flip rapidly between different epochs, themes, geographic locations, and voices. The text is littered with quotes and/or paraphrased borrowings from an exceptional range of sources, each of which Bayer cites in an Index that takes up a quarter of this very short book. The book is ostensibly about the final days of Vitus Bering (1681–1741), the Danish cartographer for whom the sea that separates Siberia from North America was named. During an ill-fated scientific expedition, Bering died a miserable death on an island that now bears his name.

Written in the 1950s, Der Kopf des Vitus Bering was not published until after the suicide of its thirty-one year old author in 1964. Bayer, a member of the small number of post-war Viennese experimental writers who came to be known as the Weiner Gruppe, used the dire circumstances of Bering’s death (health issues, a ruined ship, terrible weather, a deserted island) as the pivot around which he could spin an equally dire worldview of the human condition, which he depicts as an unending history of tyrannical cruelty, cannibalism, disease, and death. As Bayer says in the Foreword to his book, “my choice of the figure vitus bering should only be viewed as a fixed point from which to establish various connections, just as a fisher casts a net in the hope of making a catch.”[5] (Bayer didn’t use capital letters in his book.)

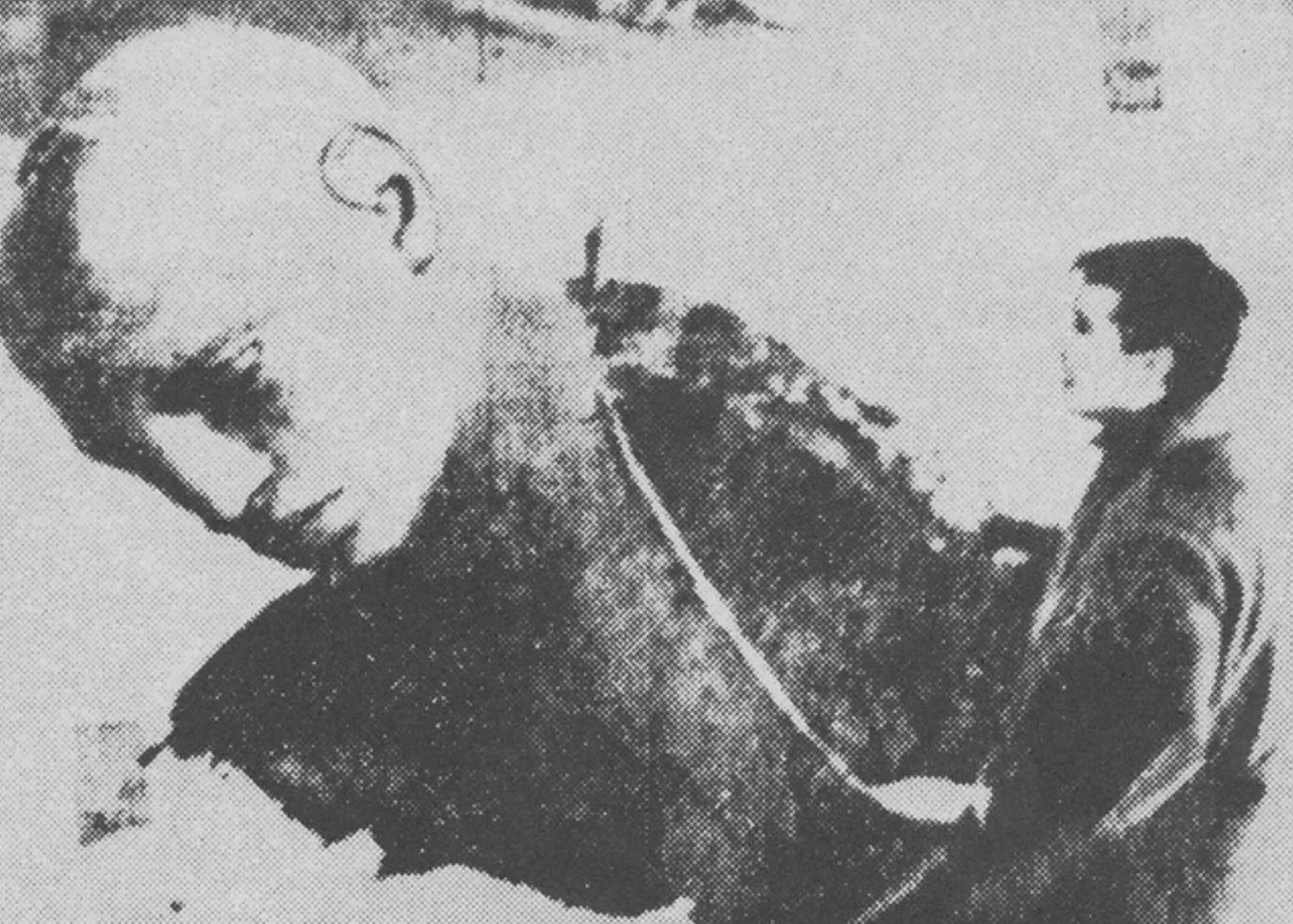

Bayer’s text begins with a sketchy photograph that depicts a man standing next to a larger-than-life statue of the head and torso of a male figure. The sculpture appears to have fallen forward. Walter Billeter, who translated Bayer’s book into English (The Head of Vitus Bering: A Portrait in Prose), writes in an afterword that Bayer borrowed the photograph from a newspaper (the half-tone dots are clearly visible) and that it shows “the fall of an oversize Mussolini bust.”6 Bayer might have amplified the already poor quality of this photograph of Mussolini so that the statue could appear to be the image of any overthrown tyrant. (It is, for example, eerily reminiscent of photographs made at the time of the April 2003 toppling of the statue of Saddam Hussein in Baghdad.)

Bayer completely ignores the factual and historical circumstances of this image. Instead, he uses it to set the stage for the radical narrative that follows. By repurposing an image from the mid-twentieth century and placing it at the opening a text about a man who lived two centuries earlier, the photograph signals that Bayer will forego any sense of traditional chronology or continuity of place in the text that follows. The photograph also affirms Bayer’s determination to dramatically reimagine what a “portrait” can be. If anything, the text feels more like a psychological self-portrait of Bayer than a portrait of Bering, who only figures on a handful of pages. As Billeter notes, “the prose portrait presented here is not of Vitus Bering, but of his head. The head is the seat of consciousness, the theatre where reality takes place.”[7] To further complicate matters, it is not definitively clear which of the two figures in the photograph might be associated with Vitus Bering or whether neither is. Indeed, it might not be inconsequential that the man who seems to have pulled down Mussolini’s statue bears a striking resemblance to Bayer himself.

Photograph Five: The Found Snapshot

Dubravka Ugrešiƈ’s The Museum of Unconditional Surrender (New Directions, 1999)[8] is a novel about what it means to be an exile. The unnamed narrator, currently living in Berlin, slowly draws the reader into a narrative about her new life in Germany and the lost world of her pre-exile memories of Eastern Europe. Ugrešiƈ likens her novel to a family photograph album. “A photograph is a reduction of the endless and unmanageable world to a little rectangle. A photograph is our measure of the world. A photograph is also a memory. Remembering means reducing the world to little rectangles. Arranging the little rectangles in an album is autobiography.” As one character quips, “refugees are divided into two categories, those who have photographs and those who have none.”

Ugrešiƈ, who was born in Yugoslavia, left what was then Croatia in 1993, going into self-imposed exile. In The Museum of Unconditional Surrender, she writes extensively about photography, exploring the complex “symmetry between photographs and remembrance” and discussing numerous photographs that are not reproduced. The book has an epigraph from Susan Sontag’s On Photography, part of which reads: “all photographs are mementos mori. To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s mortality, vulnerability, mutability.” Roland Barthes took a slightly different view by saying rather definitively that “The Photograph does not call up the past (nothing Proustian in a photograph). The effect it produces upon me is not to restore what has been abolished (by time, by distance) but to attest that what I see has indeed existed.”[9] I quote this because I think that Ugrešiƈ would disagree.

Ugrešiƈ also realizes that memory is fragile and that photographs can actually supplant memories, they can make the mind fixate on that which was photographed rather than that which was seen. As her narrator returns from a trip during which she had made many photographs, she wonders “what I would have remembered and how much if I had not taken any pictures.”

References abound to photographs and photograph albums in The Museum of Unconditional Surrender. And the act of making photographs becomes a rich metaphor for other human activities. Ugrešiƈ’s narrator makes mental photographs with the snap of an eye, while another character builds up a “verbal album” in which her memories are a noticeable improvement on reality. Photographs can even be made to lie. When one character discovers that his father fought “on the wrong side,” he simply altered his father’s portrait. “A little line here, a little smudge there and his father’s hated uniform blurred into an indistinct suit.

Ironically, the only photograph reproduced is not of the narrator’s own family or friends. It is an anonymous photograph she has found. Across from the book’s title page is a grainy image of three women standing waist-deep in water. The caption below the photograph reads: “Photograph of unknown swimmers. Taken on the Pakra River (Northern Croatia) at the beginning of the century. Photographer unknown.” This image is described and referred to a number of times in the book, but as early as the second page Ugrešiƈ tells us that this is her “fetish photograph” and that the Pakra River was very close to her childhood home.

The narrator tells us “I always carry the photograph around with me, like a little fetish object whose real meaning I do not know. Its matt yellow surface attracts my attention, hypnotically. Sometimes I stare at it for a long time, not thinking about anything. Sometimes I plunge attentively into the reflection of the three bathers mirrored in the water, into their faces which are looking straight at mine. I dive into them as though I am about to solve a mystery, discover a crack, a hidden passage through which I shall slip into a different space, a different time.”

In a 1985 essay “Photography and Fetish,” Christian Metz wrote: “the photograph, inexhaustible reserve of strength and anxiety, shares, as we see, many properties of the fetish (as object), if not directly of fetishism (as activity). The familiar photographs that many people carry with them always obviously belong to the order of fetishes in the ordinary sense of the word.”[10] What makes this particular image such an odd choice for a fetish is that the narrator knows nothing about the subject of the photograph. But because the three women in the photograph are totally unknown to her, as was the date and reason for them to be in the Pakra River, the narrator is thus free to read any narrative or meaning into the image that she wishes. Not only that, the meaning can change or, as the narrator suggests, the photograph can simply be an object that induces a meditative state.

Ugrešiƈ contrasts this real photograph of three women in the Pakra River with an “empty photograph” of another group of women – herself with five of her girlfriends. “Our empty photograph was taken several years ago at a dinner which I want to remember. It is also perfectly possible that it was never taken, it is possible that I have invented it all, that I am projecting on to the indifferent white expanse faces which do not exist and recording something which never occurred.”

Conclusion

How images function within literary texts is the subject of considerable scholarly attention. My goal in the case of these five books is to examine the basic relationship between images and text and to ask how does the image impact the reader’s understanding of the text? For me, the answer to this question lies along a spectrum that runs from something like “Has no impact” to “Dramatically changes how I read the text.” Jeff Jackson’s torn photograph serves as a symbol of the inner turmoil of his main character and suggests that the main character has literally opened himself up, ripped himself apart, in order to write his own story. Nicholas Rombes conjures up a half dozen wildly imaginative film scripts that might account for the single, rather mundane photograph in his book. Wright Morris repeats one photograph fourteen times to locate his text in time and in location. His image echoes the multigenerational story that his book tells. In each of these three cases, the photographs would seem to be inessential to the way in which I, at least, read these texts. That is to say, the inclusion of these images adds to the level of information given to the reader, but does not significantly alter the way in which the reader consumes the text. Perhaps it is fair to say that these images operate on the level of a typical book cover image. They tell us something vaguely accurate about the book inside, but they don’t actually alter our reading of it. At the same time, none of these images is used purely as illustration, to show us what something in the text looks like.

In the remaining two books, the image/text relationship is farther down the spectrum. The puzzling image that Konrad Bayer chose to open his book dramatically complicates the text that follows. Because the image bears no obvious relationship to the text, it forces the reader to ponder any number of possible image/text relationships and the implications each might have. Finally, Ugrešiƈ builds an entire book around an image and discusses at some length the implications of that image for her narrator. Obviously, the book could be published without the image, but I think Ugrešiƈ must have felt that by reproducing the photograph her readers would have an opportunity to come under the same sort of spell that it cast upon her narrator.

Until my previous sentence, I have deliberately tried not to stray into the whole issue of what might be called the aesthetic power of these five images, which is another discussion entirely. By this I mean essentially what Roland Barthes describes as the studium and the punctum of an image. Studium might be thought of as everything which falls under the rubric of the formal aesthetic content of an image – framing, lighting, composition, etc. While punctum is the power that any particular photograph might have to “prick” a particular viewer, causing an emotional response of the kind that made Ugrešiƈ’s narrator make a fetish of an anonymous snapshot.

[1] The artist who created the altered photograph is credited as Michael Salerno, who describes his work as 10 Chris'an Metz, “Photography and Fe'sh. October, Vol. 34. (Autumn, 1985), pp. 81-90 “kiddiepunk.”

[2] On the copyright page for The Absolution of Roberto Acestes Laing the photograph of the film still is credited to the collection of the Museum of the City of New York. It apparently shows two employees of the Empire Film Company in their New York City offices in 1910.

[3] Roland Barthes. Camera Lucida. Farrar, Straus Giroux, 1981, p. 67.

[4] Ibid. p. 73.

[5] Konrad Bayer. The Head of Vitus Bering. London: Atlas Press, 1994, p.7. There are two different English-language editions of Bayer’s book, both translated by Walter Billeter. The first translation was issued in 1979 by the publishing house Rigmarole of the Hours, Melbourne, Australia. It bore the full title of The Head of Vitus Bering: A Portrait in Prose, but did not include the brief Foreword by Bayer. The Atlas Press edition, a “revised version” of Billeter’s translation, reinstated Bayer’s Foreword but eliminated the book’s subtitle and Billeter’s short text on Bayer.

[6] Walter Billeter, “On Konrad Bayer.” The Head of Vitus Bering: A Portrait in Prose. Melbourne: Rigmarole of the Hours, 1979, p. 74.

[7] Ibid.

[8] The Museum of Uncondi+onal Surrender was originally wriaen in Croa'an, but its first publica'on was as a transla'on into Dutch in 1997.

[9] Barthes, op. cit. p. 82.

[10] Christian Metz, “Photography and Fetish. October, Vol. 34. (Autumn, 1985), pp. 81-90

Terry Pitts is a retired art museum director and curator. He is the author of a number of books, exhibition catalogs, and essays, mostly on the history of photography. He has curated more than fifty exhibitions for museums in the US and Europe. He studied literature and library science at the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana, and has an MA in art history from the University of Arizona. Since 2007, he has written the blog Vertigo, where he writes about contemporary literature and photography. He lives in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.